How to Play Go

The Way to Go

by Karl Baker

How to play the ancient/modern Asian Game of Go

OF BAFFLED STUDENTS

American Go Association

Note to the Seventh Edition: This version of The Way To Go has been updated to be consistent with the 1991 AGA Rules of Go.

Preface

The game of GO is the essence of simplicity and the ultimate in complexity all at the same time. It is taught earnestly at military officer training schools in the Orient, as an exercise in military strategy. It is also taught in the West at schools of philosophy as a means of understanding the interplay of intellect and intuition.

Learning go is easy. Mastering go is a delightful, never-ending challenge.

In this little gem of a book, Karl Baker has created a masterpiece of simplicity and directness that should prove a great blessing to the interested, but as yet uninitiated, beginner. For all their simplicity, the rules of go are nevertheless strange to the neophyte. The beginner will find this step-by-step manual a tremendous help in understanding the basic principles, so he can quickly get on with the fun of the game.

As a home-session primer for the beginner to prepare himself for his first game, this booklet will be invaluable. It will prove a godsend to both student and teacher.

Roger B. White

American Go Association

Contents

Chapter One - The Procedure for Playing Go

Chapter Three - Ending the Game

Chapter Five - Go Proverbs for Beginners

Introduction

Go is a game of strategy. Two players compete by placing pieces, called stones, on a board lined with a simple grid, usually 19 by 19. Each player seeks to enclose areas with his stones, much like partitioning a field with sections of fencing. Further, each player may capture his opponent's stones. The object of the game is to control more of the board than the opponent, a simple goal that leads to the elegant and fascinating complexities of go.

A traditional floor board, stones and bowls.

About The Game

Go originated in China about 4000 years ago. Japan imported go around 700 A.D. Players in eastern Asia have excelled at the game throughout modern times. Go reached the Western hemisphere in the late 1800's. Completely logical in design, the game of go has withstood the test of time. Today go survives in its original form as the oldest game in the world.

Go is a game of skill involving no elements of chance. Each participant seeks to control and capture more territory than the other. The overall level of decision-making quality invariably determines the outcome of the game. All the play is visible on the board. Play begins on an empty board, except in handicapped games (the less-experienced player generally receives an equitable head start). The action of the game is lively and exciting, jumping from battle front to battle front as each contestant seeks an advantage of position.

From the first move each player builds a unique formation. In fact there is so much room for individual expression that it is believed no game of go has ever been played in the exact pattern of any previous one. There are over 10200 different patterns available. This number is vastly larger than the estimated number of atoms in the entire universe.

A game of go can achieve a wonderful artistic intricacy, born of an individual's intrinsic creativity and realized in the significance of the shapes that he creates on the board. Go is an aesthetic adventure of more importance than the mere winning or losing.

However, in every game each player wins to some degree and necessarily loses to some degree, yin and yang. The runner-up can claim a gratifying share of the accomplishments in nearly every game of go.

Action on the go board reflects a personal effort toward balance and harmony within, a spiritual as well as practical ideal. Success on the board is related to success in this inner game. Go inevitably challenges and expands a player's ability to concentrate. The compelling dynamics of a game tend to become completely absorbing.

The situations that arise from the simple objectives of go are complex enough to have enthralled researchers of computer science and artificial intelligence for over 50 years. Only recently have computers with neural networks, and teams of programmers been able to successfully challenge go professionals on the board. Effective go strategy is sublimely subtle. For example, a player may entice an opponent into taking a series of small victories, thereby ensuring a less-obvious but larger triumph for the strategist. Greed and headlong aggression usually lead to downfall. An easy solution may succeed immediately but later prove to be a severe liability. Miscalculations are rarely final; rather, success often hinges on effective recovery from adversity, a spirited willingness to roll with the punches. The combination of local judgment and global thinking capability necessary in high-level games is largely what challenges computers when faced with an experienced human opponent.1

Go is a cooperative undertaking. Players need each other in order to enjoy the excitement of a challenging game. Unless an opponent offers a good tussle there is no game – no disappointment but then no opportunity either, no risk but no reward. Traditionally, go players value their opponents; a spirit of respect and courtesy ordinarily accompanies a game.

Perhaps most importantly, go is a means of communication between two people, a friendly debate, point-counterpoint. The play of each piece is a statement, the best statement that the player can make, and each is a response to the whole of the composition. Each play may form a simple or subtle reply, expand on other statements, or begin exploring new areas. The potential intricacy of the interaction seems to be unlimited.

Players of any skill level can enjoy go. Two beginners playing together can experience as much excitement as two veteran players. A game of go can generate in the players an amazing range of emotions. Indeed, the promise of excitement is the motivation for working through these first chapters on The Way to Go.

- The fundamental arena of go is one person facing another but there are now events for team go (3 players on each team), and pair go (2 players, one male one female, alternate turns while playing another pair of the same composition). Computer programmers are now enjoying other forms of go - one program competing with another for the highest rank, computer versus computer, and human versus computer.

"Go is a ballet of complementary patterns intertwining across the board."

CHAPTER ONE

The Procedure For Playing Go

These chapters present a series of questions designed to lead to an easy understanding of go. Look at the question and try to answer it before looking at the solution. Cover the answer with your hand, or a piece of paper, to increase the challenge if you like. Try your best. Don’t worry if your first answer is wrong. Re-read the explanation carefully if you made a mistake, and it should become clear.

To Begin

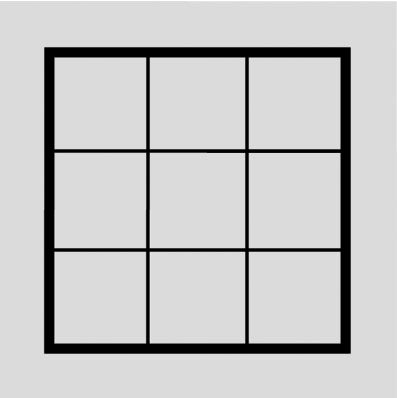

The go board has horizontal and vertical lines that criscross. Each time one line touches another they form an intersection or point. The tournament board is 19 lines by 19 lines and 361 points. The standard beginner board is 9x9 and 81 points. Boards in this booklet are of various sizes.

|

Problem: How many points show in the examples below? (Please note that some of the illustrations show board edges and some do not.) |

Dia.1

Answer:

Four is correct -

Dia. 2

Answer:

Twelve. Remember to count the point in the corner.

Dia. 3

Answer:

Sixteen.

In the game of go, as in these examples, ignore the spaces and pay attention to the points.

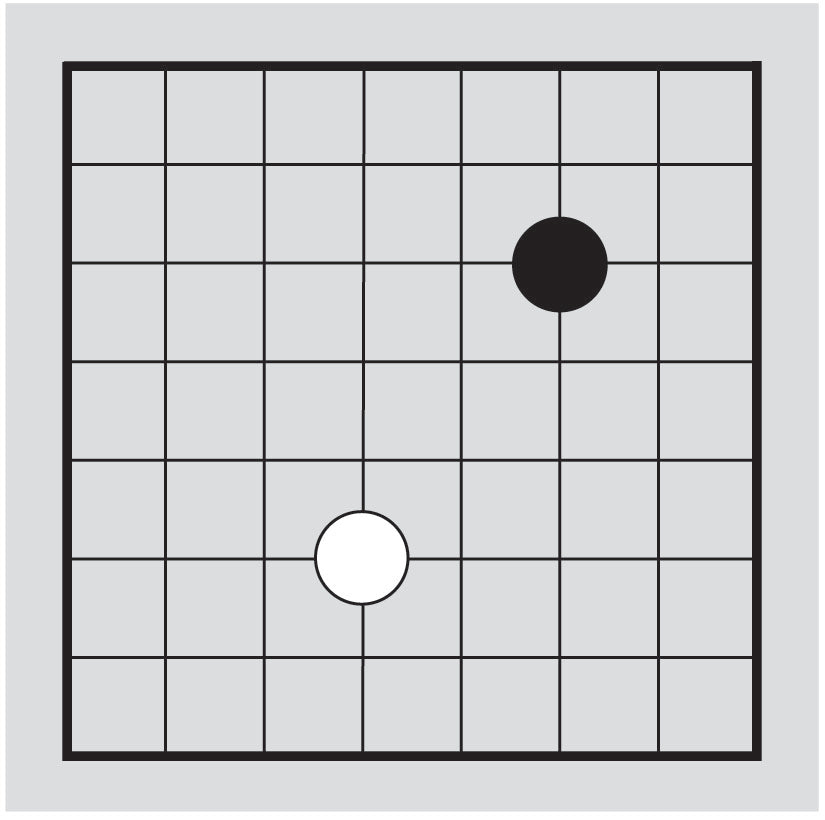

Each point is valuable. The object of the game is to control more points than your opponent. Players control points by occupying them with their stones, or by surrounding them (completely fencing them in). Play begins with an empty board. One set of stones is black and one is white. The player who takes black plays first and white must play or pass last.

The players alternate placing stones, building their positions on the board by placing one new stone at each turn. The stones are placed on the points. Once a stone is placed it is never moved to another point. When a player decides there is no benefit in placing another stone on the board, the player passes a stone to the opponent, signaling an intention to end the game.

Following are three diagrams that show a game developing through six turns: black, white, black, white, etc.

Dia.4

Dia.5

Dia.6

Notice that the white stones begin to combine, just as the black stones begin to build upon each other. It is too early in this game for any points to have been surrounded, but Black expects to enclose some territory on the right while White intends to enclose some on the left. The sequence continues from here until the game ends (illustrated on page 36).

The Mechanics

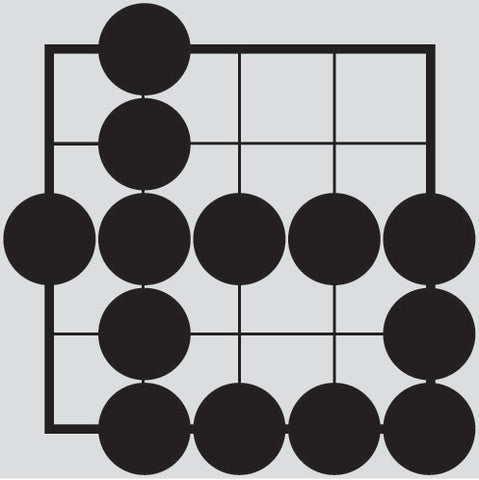

Each point on the board has lines extending from it. The very next point along a line is an adjacent point. Points are adjacent only along the lines. Any point along a diagonal is not adjacent. Each empty point adjacent to a stone is a liberty.

| Problem: How many liberties does each stone have? |

Dia. 7

Answer:

Four. Review the preceding paragraph if this is not clear.

Dia. 8

Answer:

Three.

Dia. 9

Answer:

Two. Notice that stones along the edges and in the corners of the board have fewer liberties available.

Liberties are as important in go as breathing is in life. Ahead we will be concerned with liberties again and again.

Forming Connections

Once a stone is placed on a point it is never moved to another point. When another stone of the same color is placed on an adjacent point, the two stones are connected. Once connected, stones form an inseparable unit. A single stone or any number of connected stones can make up a unit..

| Problem: How many units are there in each of the following diagrams? |

Dia. 10

Answer:

One unit.

Dia. 11

Answer

Three units.

Notice that stones touch another of the same color when they are connected. To check connections at a glance look for stones that touch. A gap between stones announces a separate unit.

Dia. 12

Answer:

Two units, one black and one white.

Dia 13

Answer:

Six units, two white and four black. Remember that stones connect only along lines, they do not connect along diagonals.

Dia 14

Answer:

Nine units, four white and five black.

Connected stones share liberties, so they have as many liberties as there are unoccupied points adjacent to the entire unit.

| Problem: How many liberties do the connected stones below have? |

Dia. 15

Answer.

Eleven.

Dia. 16

Answer:

Ten.

Reread the explanation above if this is not clear.

Capture

Placing stones so that they occupy all the liberties of an opposing unit results in the capture of that unit. Captured stones are removed from the board immediately and retained by the captor as prisoners.

|

Problem: On which point must black place a stone in order to capture white and remove the unit from the board? |

Dia. 17

Answer:

C. It may help to think of a liberty as a breathing space. Without a breathing space stones smother and die. A black stone on point C produces the following position:

Dia. 18

O - one prisoner.

Dia. 19

Answer:

C.

Dia. 20

Answer:

A and B. In this example, two liberties would have to be filled before the white stone could be removed.

Dia. 21

Answer:

A. The following diagram shows the position after black plays at A. Notice that the capture opened new liberties for the black units.

Dia. 22

OOO- three prisoners.

Whenever connected stones lose their last liberty, they are all captured.

No matter how many stones in a unit, the more liberties it has the stronger it is. In Diagram 22, black gained liberties by capturing white. The other way for a unit to gain liberties is by extending.

| Problem: On which point can white play to increase the number of liberties for his nearly enclosed unit(s) below? |

Hint: Count the liberties before and after an added stone.

Dia. 23

B. White has one liberty now; a white stone at B will result in three liberties for white, one at A, one at D, and one at C.

Dia. 24

Answer:

A. White has one liberty at A; a white stone added at A will result in three liberties for white, points B, F, and E.

Dia. 25

Answer:

B. Adding a white stone at B will increase the white liberties from two to four. Confirm that a white stone on D will not increase the number of white liberties.

This one is trickier; count carefully.

Dia. 26

Answer:

B increases the count from four liberties to five.

Dia. 27

Answer:

None of these points will increase the number of liberties for the white unit of four stones.

Players often extend in order to avoid capture. The added stone itself may reach to new liberties, as in the preceding diagrams, or the new stone may connect the unit to another unit.

| Problem: On which point can black play in order to rescue the five-stone black unit, below? |

Dia. 28

Answer:

Black's endangered unit will be saved, and strengthened to four liberties (and gain access to even more), if black joins his stones by playing at point C.

Whenever a unit has only one liberty remaining, it is in atari (uh tah ree).

|

Problem: Look again at each of the preceding six diagrams. In which of them are there stones in atari?

|

Answer:

Diagrams 23, 24 and 28.

A player who has just had a unit put into atari is not required to try to protect that unit. Neither is the other side ever required to capture. Stones may remain in atari indefinitely.

As you begin to play go, it is instructive and courteous to warn your opponent as soon as a unit comes into atari. Atari is to go as check is to chess. Saying “Atari” means, “As it stands, I will be able to capture a unit with my next stone.” Saying “Atari” is not required by the rules but it is in the spirit of the game.

Race to Capture

In each game, the players spend much of the time trying to arrange escape for friendly stones and trying to prevent the escape of enemy stones. Points that lie under captured stones become the territory of the captor. Therefore the question of capture or escape is vitally important

| Problem: Where will black play in the following situation? |

Dia. 29

Answer:

Black will fill the last liberty of the white stones in the corner and remove them from the board, simultaneously opening new liberties for the endangered black stones.

Dia. 30

OOOOO- five white prisoners.

If white gets the first play in Dia. 29, white will take black,s last liberty, capturing black and saving the cornered white stones.

Dia. 31

- six black prisoners.

- six black prisoners.

"The power of stones is always measured by the number of liberties they can keep"

CHAPTER TWO

Trapped or Safe

In this chapter we will examine safe enclosures and some enclosures that are unsafe.

Safe and Secure

In go, the players always seek to encircle territory, often the same territory at the same time. Sooner or later opposing stones meet and begin to push against each other. Liberties appear and disappear with each play. The conscientious player keeps track of the security of each unit involved in a battle.

Since stones are captured when opposing stones occupy all their liberties, then it follows that stones cannot be captured if the enemy stones cannot occupy all their liberties. In the following diagrams, units with safe liberties have these liberties surrounded.

| Problem: Can black occupy all the white liberties in each of the three diagrams below? |

Dia. 1

Answer:

Yes. White has failed to surround territory and thus has no safe liberties here.

Dia. 2

Answer:

No. White has succeeded in surrounding territory. Imagine that black begins to place stones inside this white enclosure. Notice that the invading black stones will always run out of liberties before white does. Therefore white cannot be captured.

Dia. 3

No. White has completely surrounded two separated liberties. If black attempted to play on either point inside the white enclosure his stone would have no liberties, while white would still have one liberty. The invading black stone would be smothered and captured as soon as it touched the board. The white stones cannot be surrounded completely (outside and inside) because black cannot occupy white’s inside liberties.

To Escape or Not to Escape...!

Stones that retain one or more liberties but have no hope ultimately of keeping any liberties are trapped and are often referred to as dead as they stand or simply dead stones. These stones will remain on the board as long as they retain at least one liberty and with later plays in the game they might even be rescued.

| Problem: Do the black stones appear to be trapped, or dead as they stand, in the diagrams below? |

Dia. 4

Answer:

Trapped. There is no escape for this black stone, yet it remains on the board because it has one liberty.

Dia. 5

Answer:

Trapped. Black can add more stones to these connected stones in order to guide them toward the open area of the board, where they may be able to enclose territory or connect to other units. (With his turns, white may well attempt to block black’s access to new liberties.)

Dia. 6

Answer:

Trapped. These black stones are very well enclosed. Black cannot surround any points and has no realistic potential to capture any white stones. However, white could fill black,s four liberties without endangering any white stones.

Thus, we see that stones can become trapped by being loosely surrounded even if they are not completely smothered. Trapped stones are said to be dead when all their liberties can be taken, whether or not they are taken immediately.

|

Problem: How many black stones appear to be trapped on the following abbreviated boards? |

Hint: Count the liberties of each unit involved. The one with more liberties overpowers the one with fewer liberties.

Dia. 7

Answer:

One. The black stone in the upper left corner is trapped and white need only fill two liberties to remove it. Adding another black stone to it will not increase its liberties or help it escape.

Dia. 8

Answer:

Three. The two-stone black unit in the upper left has no prospect either of escaping or of enclosing territory. Also, the black stone near the center of the board has only one liberty, while the enclosing unit of two white stones beside it has two liberties.

| Problem: In each of the two diagrams above, how many white stones are trapped? |

Answer, Diagram 7:

Three. The single white stone in the lower right corner has only one liberty. The two connected white stones in the lower right corner have only one liberty. Each black unit has more than one liberty.

Answer, Diagram 8:

Three. Black's liberties overwhelm those of white in the lower right corner and in the upper right corner. White can neither escape nor surround safe liberties there.

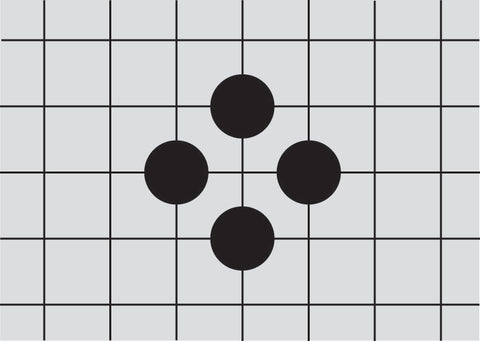

Two Eyes

A single point fully enclosed by one color is called an eye. An eye may also consist of two or more points fully enclosed by one color. Stones live by enclosing enough area to make at least two eyes. An enclosure with two eyes will always be able to retain two separated liberties and thus can never come into atari. Stones that can form only one eye, or none at all, are vulnerable to capture. (See Mutual Life addendum for exceptions.)

The following examples show some formations with two eyes and some without.

| Problem: Is white safe or trapped in each case below? |

Dia. 9

Answer:

Safe. This formation has two eyes, one enclosed area of two points and one enclosed point in the lower right. Even if all the outside liberties are filled by black, white will never come into atari.

Dia. 10

Answer:

Trapped. White has one eye and no escape route. If necessary black can fill points A, B, and C to remove the white stones.

Dia. 11

Answer:

Safe. White has two eyes; black cannot occupy either of the white liberties without placing a stone on the board that would have no liberties after the play is completed.

Dia. 12

Trapped. Black has wisely placed inside white’s single eye a stone that occupies the only point by which white could have separated the enclosed area into two eyes. If white played at either A or B, the white unit would have only one liberty and would be in atari. Confirm that black can bring white into atari by adding another black stone at A or at B. If white then captured the two black stones, black would simply place another stone inside white’s eye, finally leaving white inescapably in atari.

Of course, if white had played first on the point occupied by the single black stone (between A and B), then white would have had two eyes and would have been safe.

Dia. 13

Answer:

Safe. If an enclosed area is large enough, then it can be separated into two distinct eyes anytime it is necessary. In this case white has enclosed a single area that can be separated into two eyes with a white stone either at A or at B. If black took one of these points and white took the other, then black could not place another stone inside the white enclosure due to a shortage of liberties.

If, however, white allowed black to occupy both A and B, then white could no longer make two eyes and would die.

Dia. 14

In attempting to approach the two black stones now, notice that white would have to place white’s own stones into atari. Black can bring white into atari at any time by adding another black stone, allowing white to capture three stones, and then occupying white’s vital point as in Diagram 12.

So we see that the safest way for a player’s stones to keep liberties is to enclose at least two eyes, or enclose an area large enough to be separable into two eyes despite opposing effort. As you play, the concept of eyes will become clear.

----------------------

Congratulations! You have now learned the alphabet of go. The principle of liberties is the basis for the whole game.

" Surround enough territory and eyes will take care of themselves."

CHAPTER THREE

Ending The Game

There is one main goal in go: control more of the points on the board. This is done by (1) increasing your area, (2) reducing your opponent’s area, (3) capturing enemy stones, and (4) protecting your own stones. The winner, on balance, has always accomplished these objectives more efficiently than the loser.

Tying Up the Loose Ends

The game stops when both players pass in sequence, each handing over a stone to the opponent as a prisoner. Passing means that you see no opportunity to further any of the four goals above. Passing presumes that all the claimed territories are completely surrounded (all fence sections are in place), no stones are in atari along the borders formed by the opposing stones and there are no empty points between the opposing walls.

|

Problem: Is black ready to pass in the following diagrams?

|

Dia. 1

No. White's wall is incomplete. Black can push into white's territory through the gap in white's wall. Also, the lowermost black stone is in atari; black can save it from capture by connecting it to the neighboring black stones. Black must decide which of these two plays is more valuable.

Dia. 2

Answer:

No. Two stones are in atari, one white and one black, and the walls formed by the stones are incomplete.

Dia. 3

One black prisoner.

One black prisoner.

Answer:

Not quite. This example may look confusing at first since it brings together all the concepts discussed so far. We will simplify it by looking at one area at a time:

Look at the two white stones in the upper left corner. They have two liberties, no eyes, and no hope of avoiding capture, so they are trapped.

Next look at the two black stones in the upper right corner. They also have only two liberties, no eyes, and no hope of capturing any white stones.

Black's living stones are connected through the middle of the board. Black has an eye area in the lower right corner and another in the upper left corner.

Notice that white has two enclosures, one in the upper right and one in the lower left. White’s enclosures are not connected to each other through the middle of the board. Look to see that white has two eyes in each of these enclosures. In the upper right there is one eye in the area where the two dead black stones lie and one eye of two points just to the left of that. In the lower left corner, the single white stone divides that enclosure into two eyes (one a single point and one of three points).

Notice that no stones are in atari along the territorial borders. All the walls are complete, blocking out the opposing stones. But point X is unoccupied and black would play there in order to avoid being the first to pass, which would mean handing a stone to the opponent.

|

Problem: In each of the three preceding diagrams, is white ready to pass?

|

Answer, Diagrams 1 and 2: No, for the same reasons that black would not pass.

In diagram 3, white would place a stone at X as the last stone played in the game. The players could then agree that the game is over, the two white stones in the upper left and the two in the upper right are trapped and could be removed as prisoners.

As the game progresses, outside liberties become less important and enclosed points become all-important. Often there remain between the opposing stones some vacant points which neither side can surround but either can occupy. These are called dame (dah meh) see X on p. 32. The players continue filling dame in turn until they have occupied every dame they can. (See Mutual Life in the addendum for exceptions.)

| Problem: How many dame are there in Diagram 3? |

One. Neither side can surround point X completely.

Reaching Agreement

After one opponent passes by handing over a pass stone, the other may still play, in which case the turns continue (with plays on the board or passes) until both pass in sequence. Then the players must agree with each other about the status of each unit on the board (whether it is alive or dead as it stands). If they cannot agree, then play resumes where it left off until the situation becomes completely clear to both. In every case continued play will resolve any questions by steadily reducing the number of liberties. Eventually each unit will either lose all its liberties or it will enclose only safe points. In order to equalize the number of stones played by each side, white either makes the last play on the board or hands over the final pass stone. Experienced players will often not exchange the final two pass stones (black then white) if they know there are no disagreements regarding the status of each group.

Another way to end a game is by resignation. A player may voluntarily resign a game that has become lopsided and uninteresting to the opponent. If you lose too many stones, simply resign and begin another game. one of the players may need to take more handicap stones (or fewer) in order to facilitate a better contest (See Handicaps in the addendum.)

Scoring

Any dame that may have been overlooked do not count for either side and must be filled with extra stones, not with prisoners. To count the score, remove from the board all stones that the players agree will not be able to avoid capture (the trapped stones) and add them to the prisoner collections. Then white fills black territory with captured black stones and vice versa. The winner is the player who has more remaining empty points (or the fewer prisoners that can’t fit if neither player has any empty space). The score can be given either in the form black 12, white 9 or black wins by 3. It is also possible to count all the points controlled by each side (walls and territory) for a score of 42-39 in this instance. In an even game, since the number of black and white stones played is equal, the result will be the same by either method.

| Problem: How many dame are there left to occupy in order to complete the following game? |

Dia. 4

O - one white prisoner.

Answer:

Three. Dame do not affect the number of surrounded points, but neglecting to fill a dame in turn will cost a player a pass stone. In this case black would fill two dame and white one. Then white will pass a stone, black will pass a stone and white will pass the final stone.

Dia. 5

OO - two white prisoners.

![]()

![]()

![]() - three black prisoners.

- three black prisoners.

(note beginning of this game on page 5)

| Problem: What is the final score in each of the two previous diagrams? |

Answer, Diagram 4:

After the three dame are filled (by b, w, b) and three passes (w, b, w), the score is black 6, white 4. Black wins by two points. The result is the same if you count one point for every intersection controlled by black (19) and by white (17).

Answer, Diagram 5:

The score is black 14, white 18. White wins by four. Note that each pass stone was counted as a prisoner in this example.

It is easy to see why enclosed points are vital: They enable stones to live, and they are counted to determine the final score.

"Action on the go board can take place anywhere at practically any time. Surprise plays a major role."

CHAPTER FOUR

The Rule Of Ko

The word ko means eternity. In go, a ko refers to a common position that would allow an endless series of meaningless plays if there were no rule to cover the situation. The example below illustrates a ko position.

Dia. 1

Notice that the single black stone, separating the upper white stones from the lower white stones, is in atari. This situation is of considerable importance to both sides. The upper white stones will be trapped if they cannot connect to the lower white stones. However, if white can manage to connect solidly at point O in the next diagram, then black will relinquish three enemy stones along with the points they occupy.

White can capture the single black stone by playing on point K and taking its last liberty.

Dia. 2

Now the single white stone is in atari and it is black's turn to play. It appears that black can recapture the white stone by playing on point O immediately. Then white can recapture by playing on K (first diagram). Then black can recapture, then white, then black, and so on. In order to prevent this meaningless sequence, there is a rule that prohibits a play that repeats the prior position of stones on the entire board. A player may recapture in ko only after there has been at least one play elsewhere. This simple rule prevents a possible stalemate and is the same for all repeating sequences. (See Ko Threat in the Addendum.)

| Problem: In the diagram below, assume that black has just captured a white stone from point K. |

Dia. 3

| Problem: Can white recapture with his next move? |

No.

| Problem: Where must white play? |

Someplace else on the board.

| Problem: What could happen if the rule of ko were not in effect |

The game could not proceed if both players insisted on capturing and recapturing and if neither would play elsewhere.

The concept of ko will become clear as you play. Now you are ready to apply your knowledge of go in a real game.

Go for it!

"The go player must contend less with his opponent

and more with conflicting impulses

and emotions within himself."

CHAPTER FIVE

Go Proverbs For Beginners:

Words To Live By

Go proverbs are general rules of thumb, guidelines to recall in the inevitable moments of doubt and uncertainty. These proverbs begin to introduce elementary concepts of go strategy and tactics. Often one or the other of them will provide excellent advice for the situation at hand, but sometimes they will be entirely inappropriate. In applying proverbs, as with any decision in go, use your best judgment.

"He Who Counts, Wins"

Each play makes important changes in the liberty count of adjoining stones, both friendly and enemy. Practice counting the liberties of each affected unit after each play. With experience counting liberties will take only a few seconds.

Corollary:

"He who doesn't count liberties will surely lose."

"Stake a Claim"

Outline territory that you intend to surround. Develop the corners first, then the sides. In the corner, the edge of the board provides two ready-made walls. The side provides only one.

Corner Territory:

Dia. 1

Notice that it took only eight stones to surround thirteen points in this corner. Compare that result with the next diagram.

Side Territory:

Dia. 2

Notice that more stones, which take more turns, surround fewer points on the side.

The middle of the board provides no walls; it takes a large number of stones to surround only a little territory in the middle.

"The One-point Jump Is Never Wrong"

Instead of connecting immediately, black plays more efficiently by extending one point (and often more) from his own stones.

Dia. 3

The diagram above shows a series of one-point extensions. Black will connect when white begins to approach this position. The one-point jump is a primary tool for outlining territory and for pushing into an opponent's outline in order to interfere with its development.

"Divide and Conquer"

Use some stones in an effort to keep enemy stones from connecting with each other. Unconnected stones are easier to chase and surround than connected stones are.

If an attempt to separate enemy stones fails, then apply the next proverb.

"Don't Throw Good Stones After Bad"

Abandon stones that seem to be pursuing a lost cause. Those stones may be useful later in the game if left alone, but they will be lost for certain if you push your opponent into smothering them and removing them from the board immediately. Stones that are trapped are much better than prisoners. Trapped stones are often useful and sometimes they even escape to live again. Prisoners are gone forever.

"Play The Big Points"

As the board fills with stones, the game proceeds roughly from the larger questions of territory and capture to the smaller ones, until there are no points left unenclosed or unoccupied.

In the diagram below it is black's turn to play. Will black benefit more from blocking the connection of the three white stones at the bottom or from preventing the connection of the single stone on the right?

Dia. 4

(Answer in the next proverb.)

"Keep Your Stones Connected"

Staying connected means keeping your stones within connecting distance of each other. Even if they are not actually touching they may be considered to be connected if they cannot be prevented from connecting. Once they have been blocked from connecting, stones are in greater danger of being surrounded and captured.

In the previous diagram white has failed to keep his stones connected and black has the choice of which potential white connection to interrupt. If black decides to block one of these units from connecting, it would be more advantageous to occupy the point just above the unit of three, putting them in atari and allowing white the option of connecting the single stone on the right.

"A New Stone Makes a New Game"

Each stone radiates power and, to a greater or lesser degree, influences all the others on the board. Respect the power of enemy stones by reminding yourself that your opponent's last play just changed the situation on the entire board. Assume that both you and your opponent are trying to make the strongest available play.

"Quick Play Yields Experience"

Keep the game moving at a good pace. There is much to be gained from making many mistakes and learning from those mistakes as the results unfold. Beginners progress quickly by playing quickly and by playing many games. In addition, it is impolite to keep your opponent waiting. Most informal games proceed at a brisk, steady pace.

"If The Go Board Throws You, Jump Right Back On."

Determination is your best ally! Errors are entirely normal. As a beginner, appreciate and enjoy your privilege to make mistakes ---- the more you make, the sooner you will excel!

ADDENDUM

Handicaps

Go is unique in the world of games because it has an elegant handicap system that allows players of vastly differing ability to play each other on an even footing. Handicaps are a fundamental part of go. Most games in clubs and homes around the world are played with a handicap. Experienced go players know their rank (as golfers know their handicap) because the difference in rank between two players indicates the number of handicap stones needed for a fair game on the 19x19 board. The goal in go is to have a good time playing. If you know you are going to win or lose, there is no real contest. In games between players of equal strength, because black has the advantage of playing first, white gets compensation for going second. On a 19x19 board this is 7½ points.

Handicaps are like a head start in a race. Either the less skilled player plays the first stone and gives no compensation to white (a one stone handicap) or plays the agreed handicap (two or more stones) as the first move before white plays. White wins all ties. If two players know who is stronger, they start off with a handicap. Otherwise, two players should play even games and if one player wins too easily, they can change the handicap by a stone (or more) until the games are close. Some players adjust the handicap if one player wins three games in a row and some adjust it after every game.

Over time the handicap between two friends can change many times as they improve at different speeds. In a club, players will find that they take handicaps from some players and give handicaps to others. There will usually be someone stronger and someone weaker than you are. A one dan amateur master - the go equivalent of a first degree black belt - is 30 ranks above a beginner! Strong players should help beginners by giving them a handicap. As the beginners become experienced, they should return the favor to newcomers. In this way, players have helped each other improve for over a thousand years.

On the 19x19 board, there are traditional handicap points indicated by the nine heavy dots, called star points. There are no standard handicaps for small boards but they often include star points. AGA rules allow handicap stones to be played anywhere on the board.

Mutual Life

Occasionally positions form which involve one or more dame that are vital to life for both sides equally (often referred to as seki). In the diagram below, the two isolated units, each with one eye, have an outside liberty in common at X. Notice that if either black or white plays on this point, both groups would come into atari. It is unlikely that either side will want to place itself in atari, giving the opponent a chance to capture on the next move. Usually, neither player will fill these dame and they will stay open throughout the game.

For scoring purposes, dame in mutual life are not counted, as neither side controls them. Any points surrounded by black or white, one each in this case, are counted under AGA rules. At the end of the game stones can either be captured or not. Mutual life is simply another way that groups may live.

Mutual life

Ko Threat

When a player is prohibited from re-capturing a ko with the next turn, the player may make a move elsewhere that will be costly to ignore. Such a move is called a ko threat.

The opponent can ignore the threat and win the ko but that will allow the player to follow up on the threat. If, instead, the opponent answers the threat, the player may re-capture the ko (allowable because the board position is different). Now the opponent is the one who is prohibited from re-capturing, the one who will need a provocative threat to continue to contest the ko. The back and forth of fighting a ko is one of the fascinating subtleties of go. Ko situations can sometimes be of little importance, but often their outcome can decide the game.

Self-Capture

Unless a stone captures an opposing unit and creates at least one liberty for itself, both Japanese and AGA rules prohibit a placement on a point with no liberties or on a point which would leave one of the player's units with no liberties. Playing a stone that would be immediately captured and taken off the board along with any connected stones is rarely a good move. However, traditional Chinese rules, and the rules developed by Mr. Ing Chang-Ki in Taiwan, do permit self-capture. There are rare cases under these rules where self-capture can be tactically useful in fighting a ko.

Rules

Go is a simple game. Still, over the centuries, slight differences have evolved in the rules used in China, Japan, Korea, and Taiwan. AGA Rules (adopted in 1991) are designed to bridge the differences, to be non-language based, and to be easier for amateur players. In particular, because of the pass stones used, it is simple to play out any end game situations until they are clear.

Beginners may meet others who have learned different rules. All go literature, books, and media come from one of the rule traditions. There is no need to worry about the differences. The play of the game is virtually the same. Almost all of the variations relate to the end of the game and how the score is counted, and they rarely affect the result. Just play!

Play Online: You may not know anyone who plays go – yet – but thousands of people are playing go on the Internet right now – and some of them are no stronger than you. Find a server you like, learn to use the “client, ” and you’ll always be able to get a game. To get started, try:

The KGS Go Server (KGS):

Friendly, all levels

http://www.gokgs.com

The Internet Go Server (IGS):

Big, many strong players

http://pandanet-igs.com

Other servers:

A list of international, turn-based, and many

more kinds of servers can be found at

http://www.usgo.org/go-internet

Play in person: Take the plunge. Find a club. Go has a great handicapping system - just play! Don’t worry about winning or losing. Some people say, “The best way to get stronger is to lose 100 games as quickly as possible!” Go players tend to like each other, so you should fit right in. If you’re lucky, you live near a club or AGA chapter. To find one go to http://www.usgo.org/where-play-go. Or, start your own group – it’s easy! To find out how go to:

http://www.usgo.org/start-your-own-go-club.

Study: If you want to improve, you’ll need to play and study. You’ll find many books on every aspect of the game. We try to list them all at http://www.usgo.org/aga-annotated-bibliography-go-books-english.

Other excellent resources include:

The Interactive Way To Go:

An extensive online tutorial

http://www.playgo.to/iwtg/en/

Tiger's Mouth:

A go website for kids, with comics, tutorials, downloads and more.

http://tigersmouth.org

The American Go E-Journal:

a free weekly newsletter

http://www.usgo.org/american-go-e-journal

GoBase: A vast resource with games, articles, news and more

http://gobase.org/

Sensei’s Library:

A 15,000 page Wiki devoted solely to go

http://senseis.xmp.net/

Vendors:

Go equipment and books can most easily be found online:

http://www.usgo.org/buying-go-equipment-and-supplies

adjacent - refers to the next point along a line on the board, p. 8.

atari - warning that an opposing unit has only one liberty, p. 18.

capture - to occupy all the liberties of a unit and remove it from the board, p. 13.

connection - stones of the same color on adjacent points, p. 9, joining one unit with another, p. 18

dame - a vacant point that neither side can surround, p. 34.

dead stones - at the end of the game, stones that the players agree cannot avoid capture, p. 23.

extend - to add a stone directly to a unit in order to reach more liberties, p. 15. Also, to reach from one unit toward another without connecting directly, p. 42.

eye - a point or area fully enclosed by one color, p. 27.

ko - a repeating situation of capture and recapture, p. 37.

liberty - a vacant point adjoining a unit, p. 8.

pass - announcement that a player relinquishes his turn (includes handing over a pass stone), p. 5 and 31.

point - a place where one line on the board touches another line (intersection), p. 4. Also, a unit of scoring, p. 35.

prisoner - a stone removed from the board when it lost all its liberties, p. 13, or handed over as a pass stone, p. 34.

safe (alive) - an enclosure of stones with two eyes, p. 27.

stone - a marker of play, either black or white, p. 5.

territory - points enclosed by one side, p. 35 and 41.

trapped stones - stones that are cut off from other units and cannot form a safe shape, p. 23

unit - any number of connected stones, p. 9.

American Go Association

The AGA is dedicated to promotion of the game of go in America. It works to encourage people to learn more about and enjoy this remarkable game and to strengthen the U.S. go playing community. The AGA:

• Publishes the American Go E-Journal, free to everyone with special weekly editions for members

• Publishes the American Go Journal Yearbook - free to members

• Sanctions and promotes AGA-rated tournaments

• Maintains a nationwide rating system

• Organizes the annual U.S. Go Congress and Championship

• Organizes the summer U.S. Go Camp for children

• Organizes annual U.S. youth go tournaments

• Manages U.S. participation in international go events

Information on these services and much more is available at the AGA’s website at www.usgo.org.

American Go Foundation

The American Go Foundation is a 501(c)(3) charitable organization devoted to the promotion of go in the United States. With our help thousands of youth have learned go from hundreds of teachers. Our outreach includes go related educational and cultural activities throughout the U.S. including support for regional and local promotions, international events, teaching programs, professional tours, the US Youth Championships, and the AGA Summer go gamps. We focus on go for children and offer free class room starter sets to youth oriented programs. We provide matching funds for youth clubs and we also pay for the reproduction of instructional materials, including The Way To Go. We depend on volunteers and our sole source of income is contributed form players and go enthusiasts. If you would like to make a tax deductible donation, or volunteer, please visit our website at www.AGFgo.org.

Shop for a Go Set

Version 1-5

© 2026 Yellow Mountain Imports, Inc.